Bioshock Infinite Turns American Religious History Into A Nonsensical Nightmare

BioShock is celebrating its 15-year anniversary today, August 21, 2022. Below, we take a look at how the religious commentary in its sequel, BioShock Infinite, lacks the sharpness it needs to resonate.

Playing BioShock Infinite at launch, several things stuck in my mind as a young Mormon. Zachary Hale Comstock, the game’s principal villain and cult leader, is a kind of Brigham Young: a fiery prophet, claiming visions and prophecies while he grasps at power. His floating metropolis of Columbia is a kind of Salt Lake City: a grim capital on the cloud, both a refuge and a prison. Though the game is drawing on a melting pot of historical and fictional inspirations, these parallels have kicked around in my mind for nearly 10 years. Creative director Ken Levine even named Joseph Smith and Brigham Young as inspirations for Comstock in an interview back in 2013. To the game’s credit, these are touchstones rather than full-on parallels. In turn, though, the depiction of Comstock and his religion lacks precision: Rather than haunting resemblance, it plays as frivolous caricature. It is that flatness that fuels the game’s best-remembered false equivalences between the revolutionary Vox Populi and the white sepulchers of Comstock’s floating city.

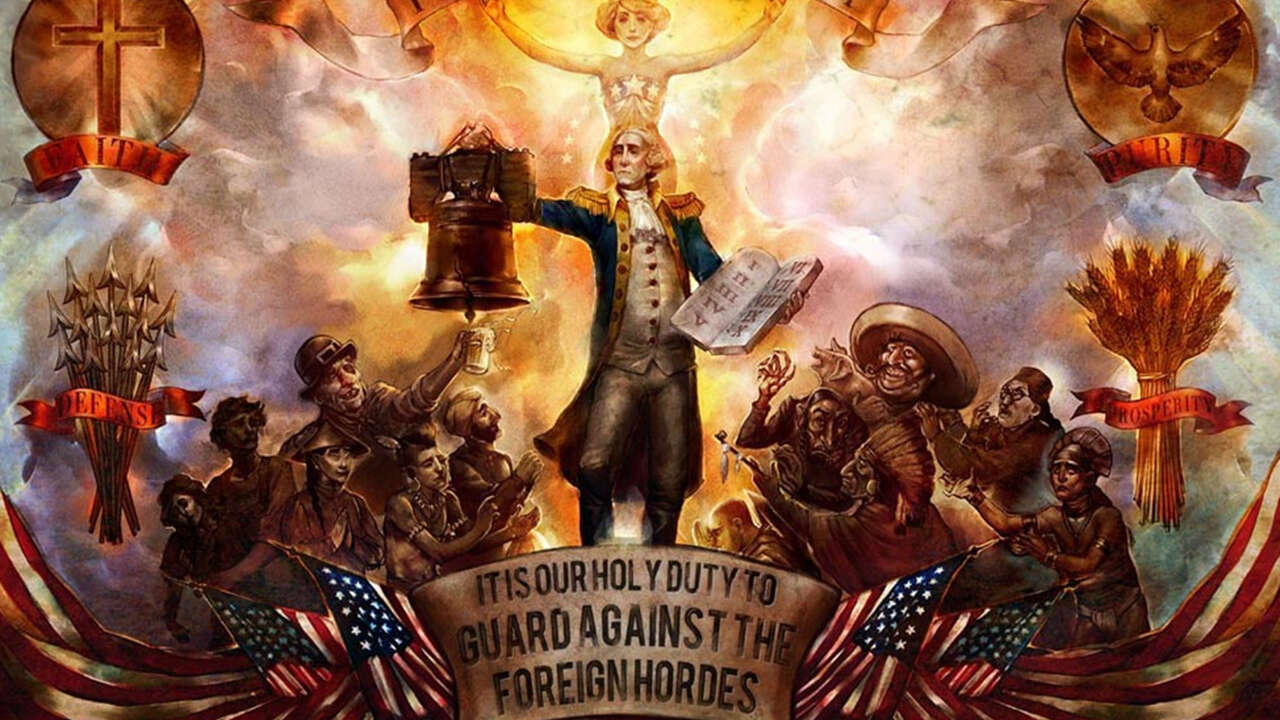

Part of that caricature is the game’s reluctance to clarify Comstock’s particular theology. We can infer that Comstock’s religion (which never gets a denominational title) believes in modern miracles, as Comstock claims to have spoken to an angel and produced a miracle child. It practices baptism by immersion. White supremacy and racism are woven into every aspect of its doctrine. It uplifts the founding fathers to the level of sainthood. Besides these basic traits, there is no context for Comstock’s religion. There are no adjacent movements or sects. Though Comstock’s journey to become a prophet began with a baptism, the game never makes clear what group he entered. This lack of specificity unties Comstock from any particular historical moment. BioShock Infinite seems to draw more from the conservative Tea Party movement–which, though politically focused, had a devotional character–more than any specific religious group, especially from the time period.

Still, the parallels to Utah and Mormonism remain. Before the game begins, Comstock’s floating city seceded from the United States. After the death of prophet Joseph Smith at the hands of mob violence in 1844, Brigham Young led a caravan to settle in what would become Utah. Thousands of Mormons would follow over the next decades. The territory was then under Mexican control until joining the US in 1850, and was the home of many indigenous peoples, including Shoshone, Paiute, and Goshute.

The key difference is, of course, that Columbia is a dream city floating in the sky. No people could have lived there before, and so Columbia imports, rather than imposes, the sociopolitical structure of a segregated United States. Though the massacre at Wounded Knee features into the game’s plot, there are no voiced indigenous characters and only racist cartoons appear in a propagandistic museum level. Intentionally or not, the floating city means that the game can largely sidestep the issue of colonial occupation.

Everything We Want in a Bioshock Movie

Please use a html5 video capable browser to watch videos.

This video has an invalid file format.

Sorry, but you can’t access this content!

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking ‘enter’, you agree to GameSpot’s

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

While Columbia’s lower classes are not explicitly enslaved, they are segregated and overworked. Columbia’s secession from the US enables it to practice “more extreme” forms of institutional racism. In history, Mormons brought slavery from the US to Utah. Three enslaved men–Hank Wales, Oscar Smith, and Green Flake–came with Brigham Young’s party to the Salt Lake Valley. There was an enslaved population in Utah until slavery was outlawed in the territories. Therefore, the history of slavery in Utah is fundamentally connected to the US’s own support of the horrific practice. Although BioShock Infinite positions Columbia as an extremist deviation from the proper United States, the Mormon settlement of Utah is best understood as a particular, if peculiar, instance of the US’s expansionist colonialism.

Columbia is curiously unified outside of the main two factions. There are people who do not neatly fit into either the revolutionary Vox Populi or Comstock’s Columbia, but they are few and far between. Mormonism, in contrast, was subject to a flurry of schisms and divisions, even in its early years. Not every Mormon traveled to Utah. Some of those who remained in Illinois formed a church of their own, under the leadership of Joseph Smith’s son, Joseph Smith III. When the church in Salt Lake City ended the practice of polygamy due to pressure from Washington, paving the way toward statehood, the church suffered a mass exodus of polygamists. The point is that Christianity, as much as any other site of meaning-making, is controversial even among its adherents. Because BioShock Infinite passes by the schisms and conflict that define American Christianity, it cannot offer a holistic criticism of its failings.

To be clear, the issue here is not a lack of “historical accuracy” or “respect for the subject matter.” BioShock Infinite is science fiction through and through; it intends to represent an alternate world. Additionally, institutions as massive as Mormonism and American Christianity can take the hit. However, these gaps between the real history and the fiction serve to distance Comstock’s faith from real-world groups. What criticism it hefts up lacks specificity and bite. What resonance it might have lacks real faith. In fact, the longer the game goes on, the more Comstock’s religion becomes about the game’s internal mythology, a backdrop to its interest in inter-dimensional drama and alternate selves.

While Comstock and crew do have clear inspiration points, the Vox Populi, led by Daisy Fitzroy, have no coherent resemblance to any real revolutionary moment, especially in the United States. They are called Anarchists, but unlike anarchism, they have no vision for a future world. All they get are slogans and blood. The game eventually labels them as too violent and moves on. The way BioShock Infinite can get to a statement like “The only difference between Comstock and Fitzroy is how you spell the name” is through these ideological vagaries. It’s telling, for example, that Columbia’s religious art never depicts Christ and the cross. Even the game’s Ku Klux Khan is clad in dark purple, rather than white. It’s also telling that Fitzroy, even more than Comstock, comes from nowhere, with no clear connection to any real-world history.

It might seem like there is a lot to unpack here and in some sense there is. The history of American Christianity, even of Mormonism in particular, carries the weight and blood of this country’s history. However, BioShock Infinite does not conjure that history, nor its weight or blood. Rather, it is content with faded caricature, with a vision of Christianity that is too fictional, self-obsessed, and distant to truly offend or resonate.

The products discussed here were independently chosen by our editors.

GameSpot may get a share of the revenue if you buy anything featured on our site.

For all the latest Games News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.