Deep inside Intel’s NUC: We visited Intel’s lab to learn the secrets of tiny computing

There’s a neat symmetry to the 10th anniversary of Intel’s NUC, which was first revealed to the world in 2012.

In ten years the NUC group (which stands for Next Unit of Computing) has sold over 10 million of its unique miniature PCs.

If that surprises you, brace yourself: Those devices are split across a jaw-dropping 600 configurations. The scope and selection of NUC flies under the radar of even PC enthusiasts, who know NUC best for its eye-catching but relatively modest line of pint-sized powerhouses.

“That’s just the tip of the iceberg,” said Brian McCarson, vice president and general manager of Intel’s NUC group. “We’re just getting warmed up.”

From concept to revolution

The NUC began with a simple concept. What if a desktop computer was just…smaller? Like, really small? Small enough to fit in your hand? The fact this idea no longer seems strange is testament to the NUC’s success – but in 2012, it was a bold concept.

PC makers had dabbled in ultra-compact design with netbooks and other, more unusual portable machines, like Sony’s Vaio P-Series subnotebooks. Yet it wasn’t clear how this could apply to the desktop.

The limitation wasn’t processors, which packed ever-more power into decreasing thermal envelopes, but design. The desktop segment remained focused on boxes built around ATX motherboards and socketed CPUs. Laptops, netbooks, and subnotebooks proved it was possible to deliver useful performance in a much smaller form factor, and a team of engineers began investigating how mobile hardware could be applied to a desktop design.

Their efforts led to a design the team internally calls the ‘4×4.’ “It’s 4 inches by 4 inches, on the board. That’s where it all started,” said Kristin Brown, commercial segment director.

The classic “4×4” design is still Intel’s most iconic NUC design.

Matt Smith/IDG

The first 4×4, launched in early 2013, was born from an internal tug-of-war. Intel’s marketing department wanted it impossibly slim; the engineers wanted to balance size with performance and serviceability. The two sides came to battle packing foam stand-ins of the ideal shape. Eventually, the possibilities were whittled down to the 4×4.

For enthusiasts, the classic 4×4 remains NUC’s most iconic design. It’s put on some girth over the years as the NUC team added new models with quicker hardware; Core i5 and i7 models came in 2015, followed by a model with Intel Iris Pro 580 integrated graphics in 2016. Still, these were just thicker versions of the 4×4 form factor. Take a quick trip to Intel’s NUC website and you’ll find the 4×4 models still hog the spotlight.

Things changed in 2018, when Intel and AMD formed an unholy alliance to integrate Radeon graphics alongside a handful of Intel mobile processors. These processors, known as the Intel 8th-Gen Core G-Series, were meant to help Intel shore up its weak graphics performance in thin powerhouses like the Dell XPS 15 2-in-1 and HP Spectre x360.

The NUC team saw an opportunity. “When Intel went down the path of partnering with AMD, it was the first time we went, oh, this is a super interesting way to build the smallest possible gaming device,” said Faisal Habib, enthusiast segment director.

The Hades Canyon NUC (front left) marked a departure from prior designs.

Adam Patrick Murray/IDG

This led to Hades Canyon. A successor to Skull Canyon, which featured Intel Iris Pro graphics, it packed a quad-core processor and up to 24 Radeon Vega compute units and delivered performance similar to a gaming laptop with GTX 1060 graphics. It didn’t look like prior NUCs, with a thicker and wider chassis and a glowing skull on the lid, but still measured less than 9 inches wide and 6 inches deep. That’s smaller than Nintendo’s Wii U game console.

I purchased a Hades Canyon NUC and use it to play PC games on my TV, a task that suits it well. But Hades Canyon – as well as its successor, Phantom Canyon – are also popular with a very specific enterprise customer.

“We’ve seen some interesting usages for it, from an Internet cafe perspective, and even an eSports hotel perspective,” said Habib. “That concept is driving some of these products, because they love the fact you can put it in a hotel room and game in a small space.” The Hades and Phantom Canyon NUCs also proved popular with those who need a small PC capable of driving numerous high-resolution displays.

Hades Canyon opened the door to a new generation of larger, more capable NUCs. Powerhouses like the most recent Dragon Canyon, which can deliver up to a Core i7-12900, are meant to turn heads – but they’re not the only reason NUC has remained relevant for a decade.

NUC’s secret success

This NUC uses a Compute Element for less compact but more modular design.

Matt Smith/IDG

The NUC group’s success is unusual. Tech giants like Intel are notorious for spinning up wild ideas that die after a few years. Remember Intel OnCue? Or its 5G modem business? What about the company’s SSDs?

PC fans might peg the NUC’s success on its flashy enthusiast projects, but it’s enterprise and business-to-business clients, not gamers and content creators, that drive the bulk of NUC’s advancements. Developers, researchers, and academics are among NUC’s most dedicated fans. A NUC might be less powerful than a full-sized desktop but, for many, performance is not the sole concern.

“There was a guy I worked with who I still keep in contact with, and he was infamous for being the guy with 26 NUCs on his desk,” said McCarson. “This wasn’t a requirement, he wasn’t asked to do that. It was just that they’re so small, so compact, so efficient, so easy to plug in.”

A NUC is small, sips power, generates little noise or heat, and is relatively inexpensive, all of which means developers can deploy NUCs as single-purpose machines. This approach eliminates a central point of failure and lets developers side-step changes to system software or hardware that might impact a workstation handling numerous projects at once.

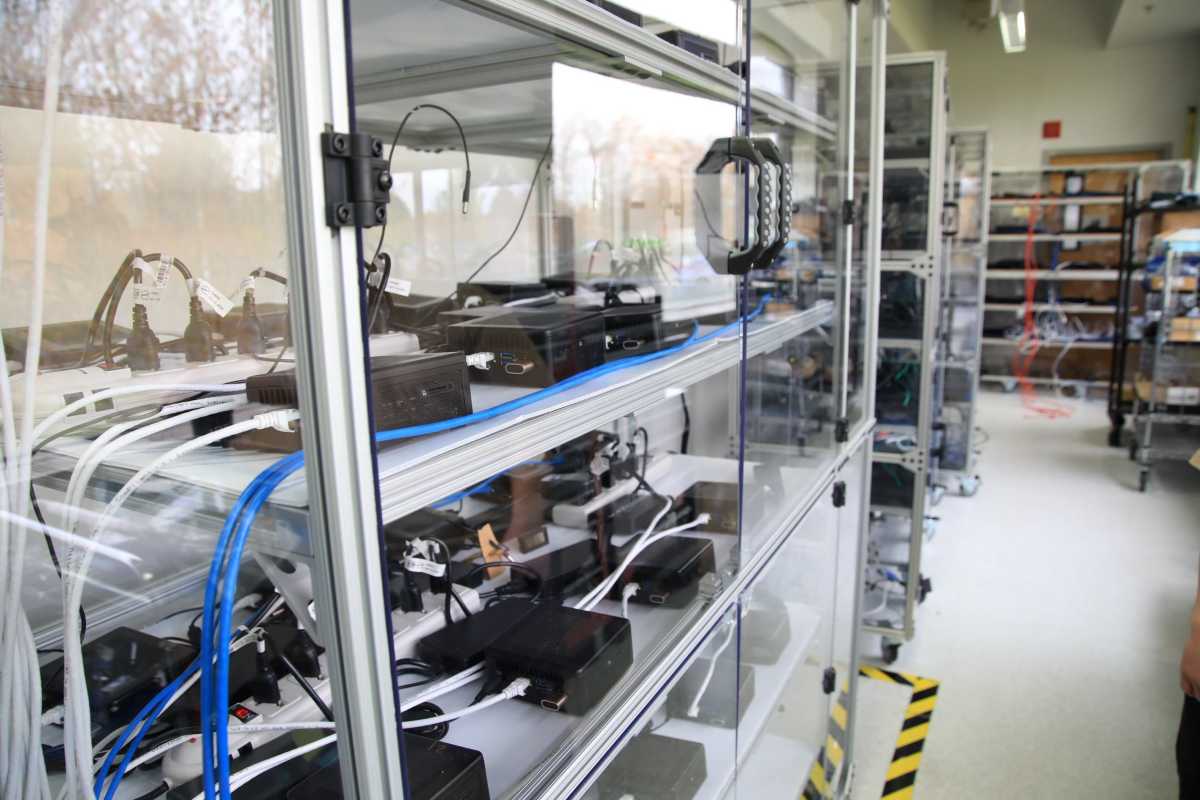

The NUC test lab uses “Bento boxes” to test dozens of NUCs at once.

Matt Smith/IDG

The NUC group is serious about reliability and efficiency. During a tour of the group’s test lab at the Hawthorne Farms campus in Hillsboro, Oregon, I was shown a series of “bento boxes” used to test dozens of NUCs at a time. Named after Marc Bento, a technical marketing engineer who designed the boxes during his internship, the boxes can be used to rigorously test NUC samples to hunt down bugs or stability issues.

The NUC group is proud of its reputation for reliability and more than once reminded me of NUC’s three-year standard warranty, a sign of confidence in an industry that often provides just one year of coverage.

This doesn’t just apply to the more well-known 4×4 NUCs, either. The group has expanded to a variety of models including passively cooled and ruggedized NUCs. Perhaps the most interesting is Intel’s Compute Element, a successor to Intel’s Compute Card.

Though it no longer slots into a convenient external connector and lacks the futuristic look of the Compute Card, the Element delivers up to 12th-gen Core i9 processors in a package barely larger than a credit card.

NUC’s Compute Element can fit into pre-packaged boards or custom hardware.

Matt Smith/IDG

“People love small compute, but in a world where we required the receiver to be exactly what we sold, it was too confined,” said Brown. “They didn’t want to always use the exact box we have. So we simplified it into the Compute Element, and started giving people building blocks.”

This takes the modular design of Beast Canyon and Dragon Canyon to a new level. While NUC sells boards for the Compute Element, users can also design their boards to precisely fit their size and I/O requirements.

“[NUC is], for the most part, these invisible solutions all over the place. Almost every fast food restaurant you go to has a little touch screen, if you pop open the back, you’ll see a NUC in there,” said McCarson.

And it’s not just fast food kiosks that could be a NUC in disguise. Intel also provides NUC hardware to OEM system builders that need a simple, affordable way to offer a small machine.

“About 80 percent of our sales is actually as white label ‘ingredients’ for machine builders,” said McCarson. “They love taking our board-level solutions and knowing they just have to drop their own shell on top of it.”

While McCarson declined to name names, he hinted these “white label” NUCs appeal most to smaller OEMs lacking the resources to build an entire miniaturized desktop design from the ground up.

More power, more problems?

It’s clear that McCarson, who was promoted to his role as Vice President and General Manager of the group just last year, wants to take NUC to a new level. That enthusiasm will be needed, as NUC’s technical challenges are likely to grow in the coming decade.

Enthusiasts know this problem too well. Top-tier hardware is growing in size and power consumption, forcing larger, more elaborate cooling systems, not to mention power supplies that deliver 1000 watts or more.

It’s this trend that forced NUC’s enthusiast group to rapidly expand the size of its quickest machines. The latest enthusiast NUC, Dragon Canyon, is only slightly smaller than a Mini-ITX PC case like the Lian Li Q58.

“When we started we were doing these graphics cards,” said Faisal Habib, enthusiast segment director, pointing to an older Nvidia Quadro card about six inches long. “But then graphics cards began to be bigger, and we can’t actually fit it anymore. We had to go and work with that with Beast Canyon, which became bigger, and it was great.”

“But then Nvidia said, no, we’re going here,” Habib gestures to a massive Nvidia’s RTX 3090 on the table. “And again, that doesn’t work.”

The ever-increasing size of PC graphics cards is a challenge for NUC’s enthusiast group.

Matt Smith/IDG

To some, the growth of the largest NUCs might seem a betrayal of the hardware’s core mission, and I pressed McCarson on this point. He sees it another way.

“NUC is now taking on shrinking bigger and bigger boxes,” said McCarson.

He admits enthusiast NUCs are growing in size and power requirements, and this is likely to continue in the future. But he points out larger NUCs still deliver an improvement over conventional PCs when they, too, are also growing in size and power consumption. “You can have more sustainable, have smaller, higher quality, and not trade off on performance,” said McCarson. “But it takes exquisite engineering.”

That engineering takes the form of modular design centered on a baseboard with a PCIe x16 slot. This idea, which arrived first in the Ghost Canyon NUC, works alongside Intel’s Extreme Compute Elements, which connect over PCI Express. This can be found not only in enthusiast NUCs but also third-party desktop PCs, such as Razer’s Tomahawk, and cases, like the Cooler Master NC100.

“We don’t necessarily care about NUC being visible if we’re helping to drive innovation for our partners, or the industry, that’s awesome,” said Bruce Patterson, Marketing Communications Manager. “A consumer may not know that a chassis has a NUC Element in it. They just say, oh, this has a Core i9, it’s a cool looking chassis. I’m happy.”

Intel’s enthusiast NUCs are growing in size but remain smaller than the competition.

Matt Smith/IDG

Even a standards-based approach has risks, however, as standards change over time—and Intel has plans to alter the baseboard used for recent enthusiast NUCs.

“We expect change to come soon. There’s been a lot of feedback from customers about what they want to see better,” said Habib. “A lot of the conversations we are having right now are about how we can reduce the number of cables in this box, and we’re wondering if we can run more of this through the baseboard.”

Intel’s Arc discrete graphics is also on its way, though the details on how it might be implemented in the NUC remain sparse.

“We’re of course working closely with the Arc team,” said Patterson. The NUC team was especially coy on this point, as no one in the room wanted to steal the Arc team’s thunder.

Whatever form Arc takes, it may not be a closely integrated, on-board solution. NUC’s enthusiast team has looked at this option for a variety of desktop graphics cards, including those from AMD and Nvidia. In theory, this might repeat the success of Hades Canyon – but the team prefers to take a standards-based approach.

“We’ve explored some ideas, like taking the desktop class graphics chip and soldering it down. Maybe there’s other ways of cooling it. But we don’t think that’s the right path,” said Habib.

He points out that while this might make enthusiast NUCs slightly smaller, it’s not a cheat code, and cooling a soldered desktop GPU with a TDP in the hundreds of watts would remain challenging. The flexibility of a standards-based approach, on the other hand, opens up options to turn up performance for the most demanding workloads—or stick to more efficient hardware for less onerous tasks.

To the next 90 million NUCs

Matt Smith/IDG

Despite these hurdles, the NUC group looks towards its next decade with a sense of optimism. The lessons of the last decade have provided the group a template for designing NUCs not just as computers but pillars of design others can buy, use, and build from.

“We want to take reference designs a step further and show not just the art of possible, but the art of possible at scale,” said McCarson. “It’s one thing to do a one off. It’s another to do it in a million unit quantity.”

And he’s serious about scale. McCarson mentioned his hopes we’ll be talking about the group shipping its 100 millionth NUC a decade from now. It’s an ambitious goal, one he seems confident the NUC group’s past experience has prepared it to achieve.

“We’re always looking at what’s next,” said McCarson. “It’s in our name.”

For all the latest Technology News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.