At the midpoint of the season, as Caleb Williams’ Heisman Trophy candidacy continued to simmer on the burner behind hotter names, the USC football program remained quiet — publicly, at least.

It was around that time that Lincoln Riley and USC director of football communications Katie Ryan had their first conversation about what an ideal timeline would look like to make a push for their star quarterback. They agreed that, when it comes to this particular award, the best option was to strategically wait for the right time to strike.

But Ryan still got to work, scheduling weekly “Heisman meetings” with about seven other USC staffers, all with an eye focused toward the UCLA game, the first of two nationally televised, high-stakes rivalry showdowns.

“We had been saying, if the UCLA game goes our way and Caleb plays well, that would be our window of opportunity,” Ryan said this week as she prepared to touch down in New York City with Williams, who is expected to win the school’s record eighth Heisman on Saturday. “Everything fell into place.”

2022 was Ryan’s first season as the Trojans’ lead sports information director, taking over for Tim Tessalone, who retired after more than 40 years in the department.

This fall, Tessalone watched from the sidelines as Williams took the nation by storm in the final two weeks of the regular season. He conjured an easy comparison to a similar scenario from 20 years ago when he led the late promotional charge for Carson Palmer.

Now, there were certainly a few differences. One, in 2002, there was no social media to blast the message efficiently across the nation. Two, while Williams entered this season among the favorites as a much-hyped transfer from Oklahoma, Palmer arrived at his fifth-year senior season as something of an afterthought.

In his first four years, Palmer had not lived up to his prep billing, throwing the same number of touchdowns as interceptions (39). USC had gone 25-24 over that period and, a year earlier, swapped Paul Hackett with Pete Carroll.

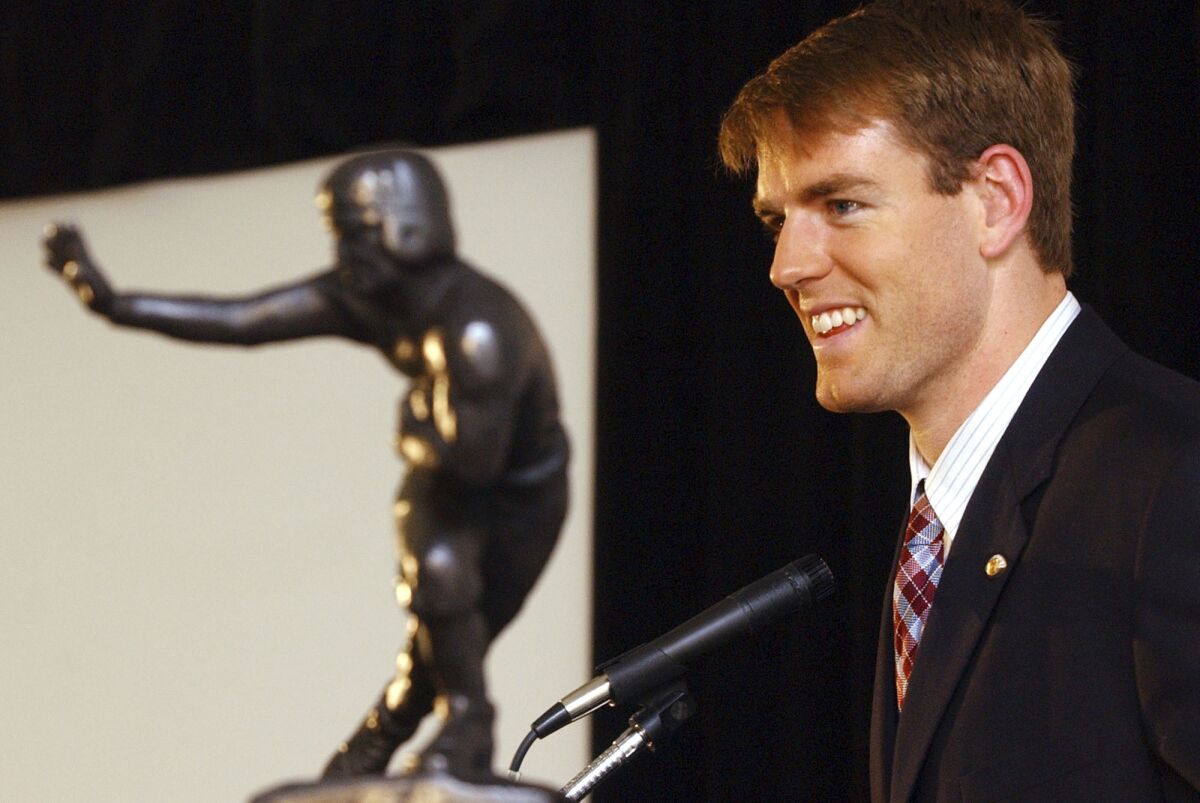

USC quarterback Carson Palmer speaks after winning the Heisman Trophy on Dec. 14, 2002.

(Mark Lennihan / Associated Press)

“He wasn’t on the forefront of being a Heisman candidate,” Tessalone said. “In fact, he wasn’t on the cover of our media guide. Troy Polamalu was, and Carson was on the back cover. If you’re going to push someone for the Heisman, you probably don’t want to do that. But Carson got off to a great start, and in the middle of the year, we all kind of looked at each other and said, ‘Should we push him for the Heisman?’ ”

Like Ryan would two decades later, Tessalone got to work. Only his involved the production of creative mailings that Heisman voters and the keepers of the sport could hold in their hands.

They made a large ticket that read “The Carson Show Ticket,” a clever nod to “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.”

“It looked like one of those oversized tickets you would use to get into a TV show or movie premiere,” Tessalone said.

Not long after, in mid-November, Times sports columnist Bill Plaschke wrote a column suggesting that Palmer was the latest West Coast star being affected by East Coast bias with Heisman voting. It was hard not to agree with Plaschke, since Marcus Allen was the last winner from out this way, 21 years prior in 1981.

“The Heisman Trophy has become the most regionally biased and unfair award in sports,” Plaschke wrote.

Palmer told reporters that week, feeding Plaschke’s frustration, “My shot of winning a Heisman Trophy is so slim, I don’t even think about it. It’s very, very rare that I would have a chance. That’s just how it works.”

Tessalone promptly emailed — he says he was just learning how then — Plaschke’s column to national college football reporters and voices with the subject line, “Hmmmm…” He made sure to talk with ESPN College GameDay and other opinion shifters about mentioning Palmer as a candidate along with Iowa’s Brad Banks and Miami’s Ken Dorsey.

Tessalone remembers USC offensive coordinator Norm Chow assuring him, “I know how to get this done.” Sure enough, Chow showcased Palmer in a 52-21 domination of No. 25 UCLA to the tune of 254 yards and four touchdowns. The next week in a 44-13 blowout of No. 7 Notre Dame, Palmer put up 425 yards and four touchdowns.

“Sounds familiar, right?” Tessalone said, referring to Williams. “Big-time performances with iconic plays at the end of the season. Both Carson and Caleb along with their teammates and coaches, obviously, dramatically turned USC’s fortunes around almost overnight.”

Palmer took the Trojans from 6-6 to 10-2 in Carroll’s second season, laying the foundation for the AP national championship the next year. Williams led USC from 4-8 to 11-2. The seven-win improvement matched the biggest one-season turnaround in school history.

But Williams also got some help from forces out East. Ohio State quarterback CJ Stroud, the favorite to start the year who remained near the top all season, struggled against Michigan in a shocking loss at home. Tennessee quarterback Hendon Hooker, who rose to favorite status after beating Alabama, did not produce in a humbling loss at No. 1 Georgia and tore his ACL in an ugly defeat at South Carolina. Michigan running back Blake Corum injured his knee against Illinois and barely played the next week against Ohio State.

Williams’ dual-threat precision tore apart the Bruins and Fighting Irish, seemingly securing the award before championship weekend.

USC quarterback Caleb Williams, left, celebrates after USC defeated UCLA at the Rose Bowl on Nov. 19.

(Mark J. Terrill / Associated Press)

His candidacy felt fresh, too, which was no accident. The first USC promotional videos for Williams on social media came after the UCLA win, and Ryan set up a feature with Fox that put Williams in the same room with past winners Matt Leinart and Reggie Bush to talk shop and let the young man show his personality.

“Like Coach Riley, I definitely believe you can oversaturate the market if you make the move too early or preemptively rush into a campaign,” Ryan said. “The timing needs to be perfect — and I think we hit the mark.

“[But] at the end of the day, should Caleb win the Heisman, it will be because of his performance on the field and because he is the nation’s most outstanding college football player.”

That said, Tessalone came away plenty impressed with USC’s promotional effort around Williams, too — especially having the foresight to show a little restraint in a world that rarely rewards it.

“As we saw with Carson, you don’t win a Heisman in September or October,” Tessalone said. “You win it at the end of November.”

For all the latest Sports News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.