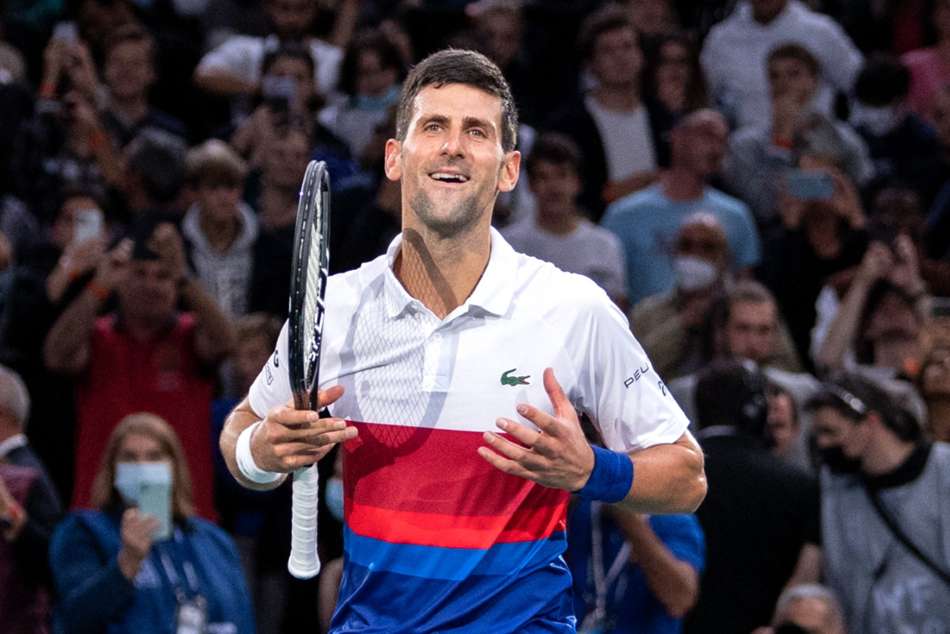

Novak Djokovic detention draws focus to Australia’s asylum-seekers

The

tennis

superstar

is

awaiting

court

proceedings

on

Monday

(January

10)

that

will

determine

whether

he

can

defend

his

Australian

Open

title

or

whether

he

will

be

deported

–

and

the

world

has

shown

keen

interest

in

his

temporary

accommodation.

His

fellow

residents

in

the

immigration

detention

hotel

include

refugees

and

asylum-seekers

who

are

challenging

their

own

proceedings

that

have

all

lasted

much

longer

than

Djokovic’s.

So

long

in

some

cases

they

feel

forgotten.

Djokovic’s

mere

presence

at

the

hotel,

a

squat

and

unattractive

building

on

the

leafy

fringe

of

the

city’s

downtown,

has

drawn

the

world’s

eyes

to

those

other

residents

and

their

ongoing

struggles

with

the

Australian

immigration

system.

Novak

Novak

Djokovic

visa

controversy:

Tennis

star’s

lawyers

say

he

was

Covid-19

infected

in

December

Refugee

activists

have

been

quick

to

capitalize

on

the

media

attention

as

one

of

the

world’s

most

feted

athletes

shares

the

hotel

and

its

sparse

amenities

with

some

of

the

world’s

most

vulnerable

and

dispossessed

people.

Djokovic

was

denied

entry

at

the

Melbourne

airport

late

Wednesday

(January

5)

after

border

officials

canceled

his

visa

for

failing

to

meet

its

entry

requirement

that

all

non-citizens

be

fully

vaccinated

for

COVID-19.

His

lawyers

filed

court

papers

Saturday

challenging

the

deportation

that

show

Djokovic

tested

positive

for

COVID-19

last

month

and

recovered,

grounds

he

used

in

applying

for

a

medical

exemption

to

the

country’s

strict

vaccination

rules.

A

decision

on

his

appeal

is

expected

Monday.

Renata

Voracova,

a

38-year-old

Czech

doubles

player,

was

detained

in

the

same

hotel

over

a

vaccine

dispute

before

leaving

Australia

on

Saturday

(January

8).

The

Park

Hotel

was

once

a

thriving

tourist

hotel,

popular

for

its

central

location

near

Melbourne’s

network

of

trams

and

across

the

road

from

the

home

ground

of

the

Carlton

Australian

Rules

Football

Club.

PTPA

PTPA

issues

Djokovic

update,

back

world

number

one

to

compete

at

Australian

Open

But

for

the

past

two

years

it

has

often

been

referred

to

as

the

“notorious”

or

“infamous”

Park

Hotel.

At

the

outbreak

of

the

pandemic

it

was

a

quarantine

hotel

for

Australians

returning

from

overseas

and

reportedly

a

source

of

a

delta-variant

outbreak

that

swept

Melbourne

and

forced

the

city

into

months

of

lockdown

while

claiming

hundreds

of

lives.

More

recently

it

has

been

home

to

travelers

of

a

different

kind:

refugees

and

asylum-seekers

who

have

been

transferred

for

medical

reasons

from

Australia’s

off-shore

detention

centers

on

Manus

Island

and

Nauru

in

the

Pacific.

There

are

32

asylum-seekers

sharing

the

hotel

with

Djokovic.

Among

them

is

Mehdi

Ali

of

Iran

who

was

15

when

he

made

the

dangerous

journey

to

Australia

by

boat.

He

had

spent

the

past

nine

years

in

an

off-shore

processing

facility

for

asylum-seekers

and

refugees,

and

was

recently

moved

to

the

Park

Hotel,

where

armed

police

guard

the

entrance

and

residents

cannot

leave.

Mehdi

says

the

hotel

is

“like

a

jail”

with

its

lengthy

confinement,

lack

of

fresh

air

and

poor

food.

In

October,

a

COVID-19

outbreak

infected

more

than

half

of

the

hotel’s

then

46

residents.

In

December,

small

fires

broke

out

on

one

floor,

residents

were

evacuated

and

one

person

was

treated

for

smoke

inhalation.

Novak

Novak

Djokovic

denied

Australia

entry:

Tennis

world,

political

leaders

react

to

‘unusual’

step

Damage

caused

by

the

fires

affected

residents’

access

to

outdoor

exercise

areas,

and

asylum-seekers

frequently

complain

they

are

confined

to

their

rooms.

Refugee

advocates

regularly

protest

outside

the

hotel,

mostly

in

small

numbers

and

unnoticed

by

passersby.

Djokovic’s

sudden

arrival

has

energized

the

protesters

as

they

seek

to

draw

global

attention

to

the

asylum-seekers

and

their

treatment

in

Australia.

An

Amnesty

International

campaign

manager,

Shankar

Kasynathan,

was

among

several

groups

protesting

outside

the

Park

Hotel

on

Friday

(January

7).

One

large

group

of

Serbian-Australians

protested

Djokovic’s

detention

while

another

smaller

group

of

protesters

celebrated

his

opposition

to

vaccine

mandates.

“The

world

is

watching

at

this

point

because

we

have

one

of

the

world’s

most

celebrated

athletes

…

under

the

same

roof

as

the

world’s

most

vulnerable

people,

namely

refugees,” Kasynathan

said.

“We

hope

that

Novak

Djokovic

will

use

his

influence,

his

support

base

to

potentially

put

pressure

on

(Home

Affairs

Minister)

Karen

Andrews

and

the

Australian

government

to

end

this

senseless

cruelty,”

he

added.

Australia

first

introduced

offshore

processing

at

Manus

Island

in

Papua

New

Guinea

and

Nauru

in

2001

as

part

of

its

“Pacific

Solution”

to

asylum-seekers

and

refugees

attempting

to

reach

Australia

by

boat,

often

with

the

help

of

traffickers.

Offshore

processing

was

suspended

in

2008

but

resumed

in

August

2012.

Since

July

2013,

successive

Australian

governments

have

said

no

refugees

will

be

resettled

in

Australia

from

Nauru

or

Manus

Island.

By

mid-2021,

about

1,000

refugees

from

the

offshore

centers

had

been

resettled

in

other

countries,

including

more

than

900

in

the

United

States.

Many

in

the

offshore

centers

have

been

transferred

back

to

Australia

for

medical

reasons

and

have

been

detained

at

places

like

the

Park

Hotel.

Djokovic

will

be

granted

his

freedom

on

Monday

one

way

or

another.

If

his

legal

challenge

to

the

cancellation

of

his

visa

is

successful

he

will

be

able

to

defend

his

Australian

Open

title

next

month.

If

not,

he

will

have

to

return

home.

For

others

at

the

Park

Hotel

there

will

be

no

such

choice.

Their

wait

will

continue.

For all the latest Sports News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.